Prison Projects

We are proud to work on innovative projects with prisoners and ex-offenders. We have previously worked on successful film and theatre projects with prisoners from HMP Hollesley Bay, HMP Norwich and HMP Whitemoor.

Currently we work with the residents at HMP Warren Hill, working with an incredible group of life sentence prisoners on drama and heritage projects as part of Warren Hill’s ground-breaking education and rehabilitation programme.

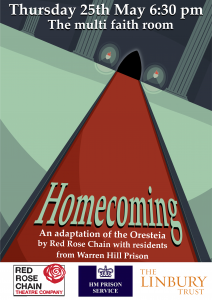

Homecoming (2023)

In 2023, we worked with life sentence residents of HMP Warren Hill to create a performance about crime, violence, and what might drive someone to take revenge. Participants drew parallels between the Greek tragedy of The Oresteia, and a modern family caught up in organised crime. The prisoners performed this piece through written word, song, and physical theatre to an audience of fellow inmates and members of the prison staff.

“I enjoyed working with the outside actors. Made me feel a bit normal for a while.” -One of the participants

The Citizen (2018)

In 2018, we worked with residents in HMP Warren Hill to create their play, THE CITIZEN. It explored the complexities of redemption and the debate surrounding the life license, drawing parallels between the prisoners’ own experiences of violent crimes and those of the Roman Gladiators who could win their freedom through violence.

The project featured in an article by Libby Purves The Times

A beacon of hope shining out from prisons

I’ve seen how groundbreaking arts programmes give hardened inmates a voice and a belief in the power of redemption

We grow misty-eyed at Nativity plays, pretty cribs and the fragile sacredness of new life, but the season’s story is not all about innocence. In every carol service the holly “bears a bark as bitter as any gall”, voices salute “redemption’s happy dawn” and the merry gentlemen, although relieved of their dismay, admit going astray. In the Provençal crib villagers bring tributes, but Le Boumian, the brigand, sneaks in amid the innocent to throw down his knife and vow to give up murdering. In a dozen incarnations from the Muppets to the RSC, Scrooge undergoes a painful moral change: Christmas spells redemption as well as merriment.

So I keep thinking about HMP Warren Hill, a category-C prison in Suffolk praised by the inspectorate as one of our best. Those in it tend to be nearing the end of long sentences; its education programmes and human relationships are exemplary, with a key worker system and interested, intelligent officers. This year I have watched daytime concerts there run by Aldeburgh Music (which is much involved and visibly contributes to morale). Prisoners perform rock and pop covers but also original songs and poetry, some joltingly personal: to write about a life blighted long ago by your own deeds is brave, and to see your newer self applauded by officers and outsiders is hopeful.

Prison arts are valuable, and I have championed drama in particular for years: Pimlico Opera, Only Connect and other projects like the former London Shakespeare Workout. You can see cramped minds and hearts opening, maybe only a crack, maybe not for long, and feel hope. If we are not to execute or exile, we must rehabilitate. Few will forget the moment in West Side Story at Wandsworth, when after the usual fun with Officer Krupke (a patient prison officer) There’s a Place For Us was sung. Not by the lovers but quietly from the gymnasium’s stark gallery by a chorus of inmates. Disciplined collaboration, with professional leads and directors for ticketed productions, has borne good fruit and led some on to better lives. But on this year’s third visit to Warren Hill I saw something different, a layer deeper.

The Citizen was a play written, debated, shaped and performed by prisoners, on their own themes and questions. There were two authors and some improvisation but the core theme was forgiveness: redemption, the possibility of full social acceptance. The issue of “life licences” is a hot one for lifers, as the state retains power to recall you for any lesser infringement, and to supervise permission for new jobs or any travel. The conviction, because of its seriousness, is thus never totally spent.

Some of the 15 or so men in the play had been studying law with a Cambridge professor. One of the writer-directors became fascinated by the Roman law under which a gladiator, a slave, could by exceptional courage and skill win his freedom and receive the wooden sword of a Rudiarius. So one strand of the play was set in ancient Rome with Gaius, a radical questioning slave, and his more conventionally careful father.

A second story was inside a prison, with men with names like Reason, Wisdom and Righteous experiencing violence and debating impulse, truth, and the conflict between orderly social hierarchy and spiritual truth. The third strand is political, as a Conservative prime minister “whose heart is at odds with his ideology” clashes with hawkish punitive advisers and a baying revolutionary crowd. The stated themes are democracy, defiance, tolerance, and above all the need for forgiveness: to belong again in society.

If it sounds artistically a bit of a jumble, indeed it was. But gripping, too. Their outside adviser was Joanna Carrick, an actor-playwright who leads the Ipswich company Red Rose Chain. It mixes professional work with a wider community of children and adults, some with vulnerabilities and risky lives, and working with the men was a continuum from that. There were, she recalls, powerful arguments about whether total forgiveness after the most appalling crimes is possible, and how to win it.

By the time you are in this kind of prison, still secure but with a focus on rehabilitation and future parole, you will have experienced the harsher kind: the ones in trouble, which our valiant and pragmatic prisons minister Rory Stewart has sworn to improve within a year. So you are aware not only of the system’s exasperating unfairness, how ex-servicemen, care leavers and the mentally ill are over-represented in custody, but of real horrors. You will know, or have been, a person who deeply deserved a life sentence.

It was extraordinary to watch the energy with which men with this hinterland tackled questions of forgiveness and acceptance. Equally striking was their passion for nation, law, democracy and duty. It reminded me of another line from our prisons minister, a man who, in youth, attempted to bring accord to Afghanistan and does not tend to sentimental optimism. “If you begin from an idea that we’re all victims, this is all miserable . . . [that] our politicians are a bunch of morons, everything’s going to hell in a handbasket, it’s no way to proceed. Everything has to begin with huge respect and affection and love for what people achieved before we came along, and how great our country is.”

In an angry and divisive year, The Citizen was just one project, in one small prison. But it felt like a beacon of hope. A bit like Christmas.